US Mayors Cite ‘Unprecedented’ Mental Health Crisis as Top Concern

Substance abuse, homelessness and access to health services are among the issues that city officials say demand more resources in a new US Conference of Mayors survey.

An “unprecedented” mental health crisis is overwhelming US cities, which lack adequate resources to address growing challenges, according to a new report released today by the US Conference of Mayors. In recent years, the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated mental health issues, particularly involving substance abuse, said a survey of mayors of 117 cities in 39 states.

“Addressing this surging mental health crisis is one of the most pressing issues facing America’s cities,” said Tom Cochran, executive director of the US Conference of Mayors, a nonpartisan organization of cities with populations of 30,000 or more. The report also cited “staggering increases in stress, depression, isolation, loneliness, and accompanying mental health hurdles faced by Americans of all ages.”

In a survey conducted this spring, 97% of mayors said requests for mental health services increased in their city in the past two years, but 88% lack resources to address the crisis. Participating cities spanned the US, and included Chicago; Seattle; Montgomery, Alabama; and Atlanta.

Substance abuse was the main cause for increasing mental health problems, 85% of cities reported. That was followed by Covid-19, homelessness and economic concerns.

Substance use disorders topped the list of mental and behavioral health problems in 65% of cities, followed by homelessness stemming from mental illness in 56%. Other challenges included shortages of mental and behavioral health workers, including school counselors, as well as a lack of access to behavioral health services.

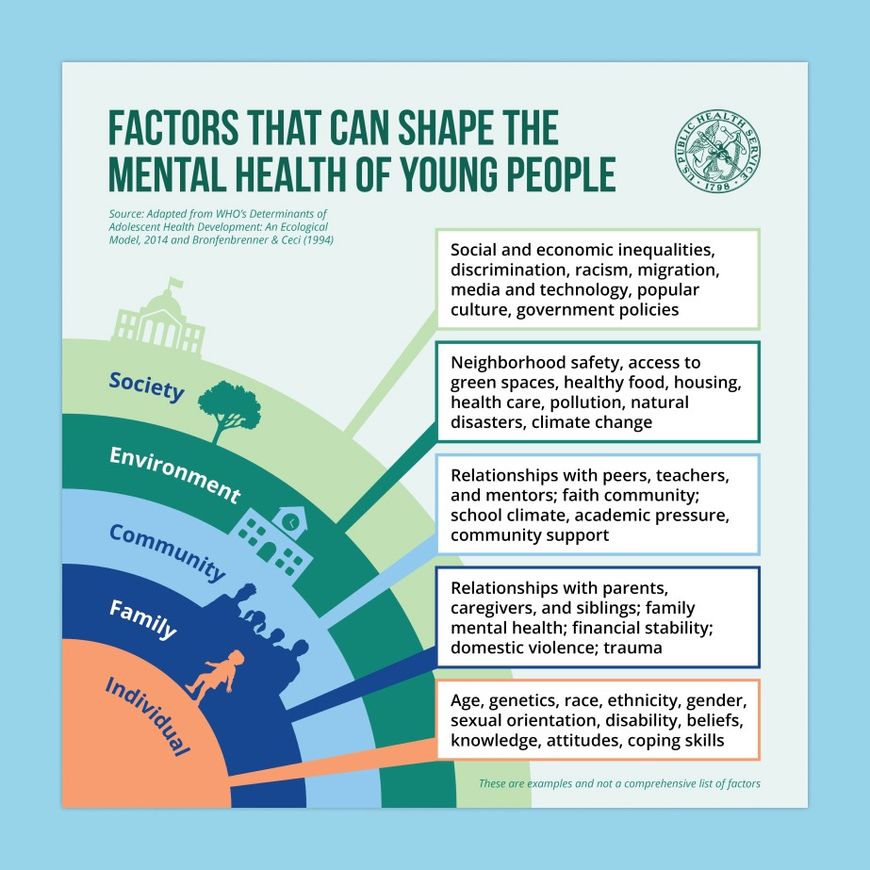

Among youth, depression is the leading primary mental health problem, according to 89% of cities. More than 43% said teen suicide is a significant problem.

Nineteen cities called for more funding for services, but several noted that most funding goes to county — not city — governments.

Although the vast majority of cities reported inadequate mental health resources, 82% have developed new initiatives and/or increased funding to mental health programs. Ninety-three percent reported they have improved their emergency response to behavioral health crises. Meanwhile, 94% of cities said their police department provides mental health programs to officers.

Examples of initiatives cited in the survey include Mesa, Arizona, where its police department is coordinating with a nonprofit crisis line and system. Since 2018, the city has increased the types of emergency calls transferred, including children with behavioral issues, second-hand suicide reports, as well as dementia, psychosis, anxiety, PTSD, and basic problem-solving help. In 2022 alone, more than 3,500 911 calls were sent directly to its crisis hotline, away from Mesa’s police and fire departments, according to the city’s survey response.

In Las Vegas, an outreach team provides services to unhoused people to divert them from emergency rooms and into appropriate treatment. A crisis response team also works with the fire department to deescalate non-emergency mental health issues.

Long Beach, California, has established mobile homeless and behavioral health services, and teams of mental health clinicians to do homeless outreach. In 2022, Hartford, Connecticut, launched a non-law enforcement crisis intervention program in response to emergency 911 calls for people in mental health crises.

City leaders from Orlando, Florida, expressed their support for the “Housing First” model as a means of addressing homelessness, and said mental health challenges are easier to address when people are housed. But respondents from the city of Fontana, California commented, “Hiding someone away in an apartment or hotel room does not cure them from mental illness. Housing first without mental health support DOES NOT WORK.” [SIC]

Officials from Issaquah, Washington, observed: “Stable housing must be coupled with other intensive support services. Housing alone does not improve mental health outcomes.” They added that for chronically unhoused people, “adjusting to living indoors is often underestimated and if housing is not accompanied by extra supports to help with the transition, people are more likely to fall back into homelessness.”