Why exercise is key to living a long and healthy life

Research shows there are a few lifestyle interventions that can effectively prolong our life and health span. One of these is exercise, but what kind, and in what combinations, and why does it help add years to our lives? Find out in our latest podcast episode.

Seemingly since times immemorial, humankind has been, metaphorically speaking, seeking the path that leads to the “Fountain of Youth” — that is ways to ensure a longer, healthier life.

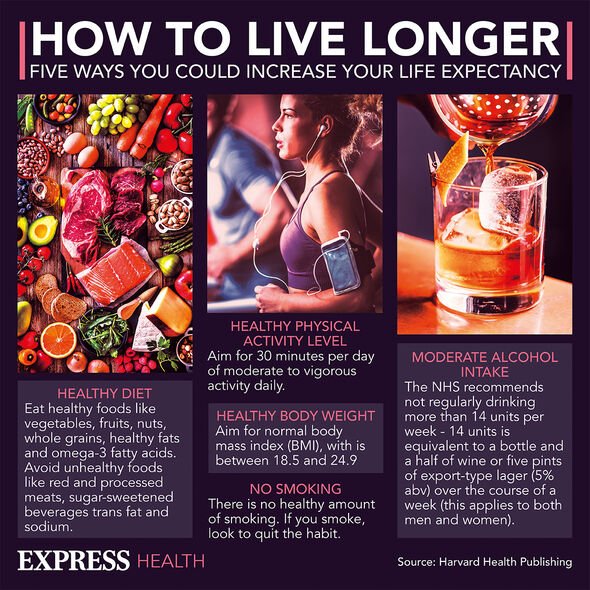

And while we may not yet benefit of any “miracle” medicines or technologies to prolong our life spans well over the hundred-year mark, many recent studies have provided strong evidence in support of the notion that simple, achievable lifestyle changes can help us stay healthy for longer and decrease our risk of premature death.

Research presented at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2023, for example, suggested that eight healthy habits can slow down biological aging by as much as 6 years.

These habits are related to diet, maintaining a healthy weight, avoiding tobacco, maintaining good sleep hygiene, managing cholesterol, blood sugar, and blood pressure, and, no less importantly, staying physically active.

Dr. del Pozo Cruz is principal researcher in Applied Health Sciences at the University of Cadiz in Spain, and adjunct associate professor in the Department of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics at the University of Southern Denmark.

In collaboration with other researchers, Dr. del Pozo Cruz has conducted various studies exploring the link between different forms of exercise and the risk of death from different causes.

Dr. Brocklesby has gained fame under the nickname “Iron Gran,” as at the age of 72, she was the oldest British woman to complete an Ironman Triathlon.

What types of exercise lower death risk?

in August 2023, Dr. del Pozo Cruz and his colleagues analyzed data from 500,705 participants followed up for a median period of 10 years to see how different forms of exercise related to a person’s mortality risk.

The study looked at the effect of moderate aerobic physical activity, such as walking or gentle cycling, vigorous aerobic physical activity, such as running, and muscle-strengthening activity, like weight lifting.

Its findings indicated that a balanced combination of all of these forms of exercise worked best for reducing mortality risk.

More specifically, around 75 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise, plus more than 150 minutes of vigorous exercise, alongside at least a couple of strength training sessions per week were associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality.

When it came to reducing the risk of death linked to cardiovascular disease specifically, Dr. del Pozo Cruz and his collaborators suggested combining a minimum of 150–225 minutes of moderate physical activity with around 75 minutes of vigorous exercise, and two or more strength training sessions per week.

Dr. Brocklesby, who goes by “Eddie,” is herself an example of the importance of combining different forms of exercise. Indeed, training and participating in a triathlon — which is an endurance multisport race where participants compete in swimming, cycling, and running — involves achieving a balanced “diet” of moderate and vigorous exercise, as well as strength training.

How little exercise is enough?

But what about people who are not nearly as athletic? What is the minimum “amount” of exercise that could help fend off some of the conditions that pose the highest threat to health?

This research suggested that engaging in vigorous exercise for only 2 minutes a day could help slash the risk of death related to cancer or cardiovascular events.

The researchers found that study participants who never engaged in vigorous exercise had a 4% risk of dying within 5 years, but introducing less than 10 minutes of vigorous activity weekly halved this risk. Moreover, their risk of death halved again for those who engaged in at least 60 minutes of exercise per week.

“A substantially lower risk of mortality was observed among individuals who had adequate levels of both long-term leisure time moderate and vigorous physical activity”, the study says, noting that higher levels of vigorous physical activity were associated with lower mortality among those with insufficient levels of moderate physical activity each week.

But this was not the case for those who already had high levels of moderate physical activity—more than 300 minutes each week.

With that, the study notes that “any combination of medium to high levels” of vigorous (75 to 300 minutes per week) and moderate physical activity (150 to 600 minutes per week) “can provide nearly the maximum mortality reduction,” which is about 35% to 42%.

Additionally, people who are insufficiently active—meaning less than 75 minutes per week of vigorous or less than 150 minutes of moderate physical activity—could get greater benefits in mortality reduction by adding in modest levels of either exercise. This means 75 to 150 minutes per week of vigorous exercise or 150 to 300 minutes each week of moderate physical activity. Doing so can reduce mortality by 22% to 31%.